Some surgeons just have it.

The calm hands. The sure movements. The uncanny ability to make complex operations look effortless.

But there’s a hidden truth within the operating room: for all the reference we give to surgical skill, we’ve never truly measured it.

Dr. Ronald Barbosa was the first to bring this to our attention during Surgical Data Science Collective’s (SDSC) Data Science Roundtable (DSRT) Series. He noted that the question of technical proficiency – what it really means, how we evaluate it – remains one of the most important and ambiguously answered in modern surgery.

There are several core competencies you are required to have as a surgeon, including but not limited to: professionalism, patient care, medical knowledge, and practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI). However, the matter of surgical skill is still assessed subjectively, rather than quantitatively.

You may have heard of the written and oral boards graduating surgeons must pass, however, there’s ‘technically’ no assessment of technical ability. “Out of all the core competencies we are required to have as surgeons, technical skills are not even on the list. Which is weird because if we were basketball players, technical skills would be no.1. But for some reason for surgeons it is underemphasized,” Dr. Barbosa states.

And yet, we know that surgeon skill plays a part in patient outcomes. Of course, every patient is unique – recovery can look different, and complications can fluctuate drastically even among the most seasoned surgeons. But for decades we’ve tried to explain these differences through case complexity, comorbidities, or chance.

To highlight the extent of the problem: the global unmet surgical need has now risen to 160 million procedures per year, and with an estimated 3.5 million adults dying within 30 days of surgery annually, finding an answer has never been more urgent.1

With this in mind, what if we started to consider the gathering evidence that technical skill may be a powerful factor in outcomes… How much does it really matter? How can we measure it?

Evidence Hidden in Plain Sight

The idea that performance affects outcomes isn’t new, but for a long time, we couldn’t see it.

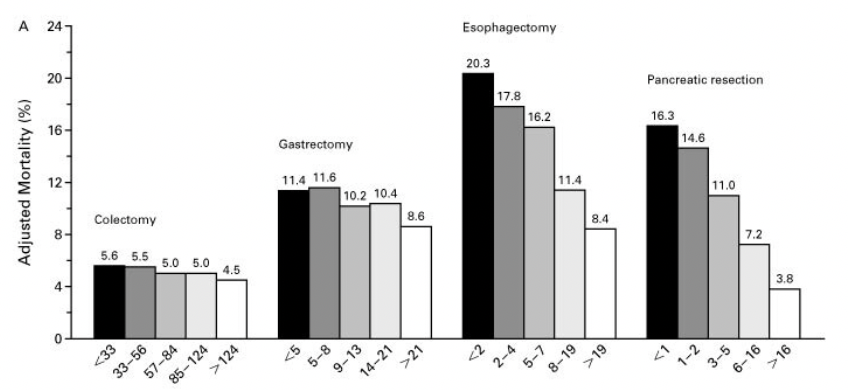

In 1979, Luft, Bunker, and Enthoven published “Should operations be regionalized?” in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), showing that hospitals performing more of a certain operation had significantly lower mortality.2 This crucial volume-outcome finding was the first to hint that something about repeated experience – perhaps technical skill – mattered.

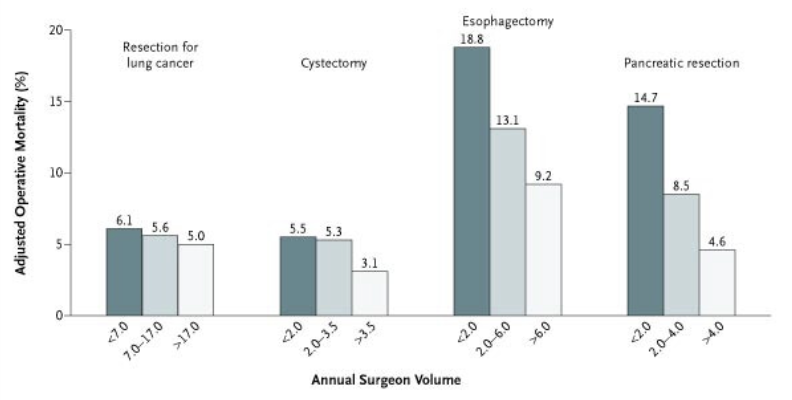

Two decades later, Birkmeyer et al. brought the focus of this question closer to individual surgeons. Their 2002 NEJM study “Hospital Volume and Surgical Mortality in the United States,” demonstrated that hospitals with higher volumes achieved better outcomes across multiple procedures.3 The following year, their “Surgeon Volume and Operative Mortality in the United States” study revealed that much of that hospital-level effect could be explained by the individual surgeon’s volume – a step closer to identifying skill as the key variable.4

We’ve already heard from Dr. Pamela Peters that surgeon case volume has a profound impact on technical skill and confidence. This is particularly evident for clinicians training in fields like Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB/GYN) where shrinking case volume has been a battle for decades. But are these parallels more pressing than we thought?

In 2013, a real breakthrough came.

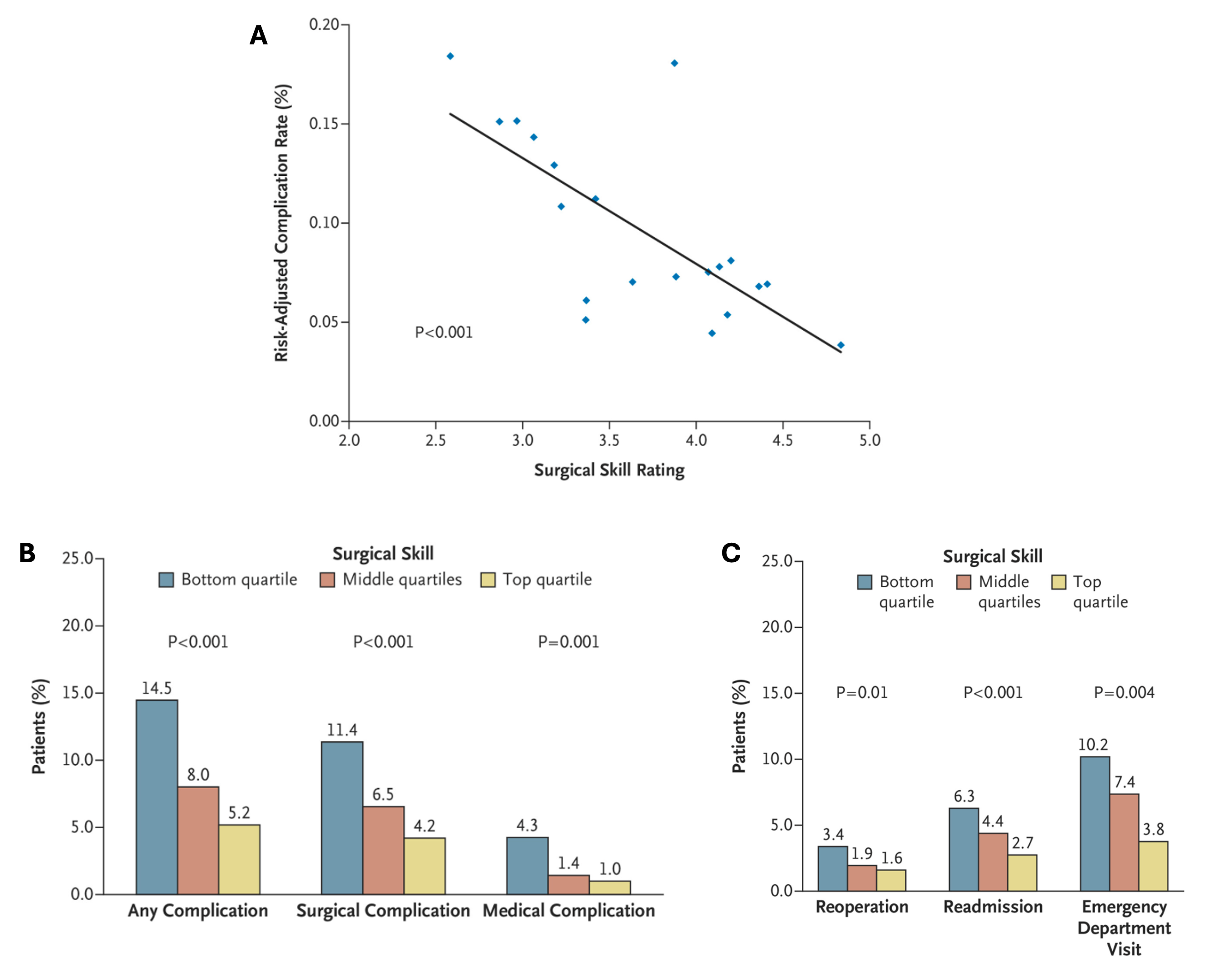

In “Surgical Skill and Complication Rates after Bariatric Surgery,” Birkmeyer et al. directly measured surgical performance for the first time.5 Using peer ratings of unedited operative videos, they demonstrated that surgeons with higher-rated technical skill had significantly fewer postoperative complications, reoperations, and emergency visits.

This was the first large-scale, direct link between measured technical skill and patient outcomes.

Subsequent studies went on to reinforce this evidence. In 2016, Scally et al. examined video-rated skill and its relationship to long-term outcomes.6 Then in 2020, Stulberg et al. followed up with a similar methodology in colorectal surgery, showing that technical skill could explain 26%, or about a quarter, of the variation in complication rates.7

26% is monumental, and an extraordinary figure in surgical data science where just a single percentage point can mean the difference between recovery and readmission.

Despite all of this accumulating data, most specialties don’t routinely measure skill in any objective way. Szasz et al. wrote in Annals of Surgery that the surgical world has shifted from time-based education to competency-based education without clearly defining what competence actually is, or how to measure it.8

So, we have a paradox: skill blatantly matters, but it is rarely quantified/measured. As Dr. Filippo Filicori stated in his DSRT: “The trends are undeniable.”

Measuring the Invisible

Part of the challenge is philosophical. Surgical education frequently prizes experience over evidence – hours in the OR, years in training, case volumes. But none of these necessarily correlate with what happens within the operative field.

How do we measure something as nuanced as tissue handling or efficiency of motion? What metrics can capture the difference between deliberate precision and hesitant overcorrection?

At recent SDSC DSRTs, Dr. Ronald Barbosa argued that as surgery becomes increasingly digital, the tools to measure skills are already in front of us. Cameras, sensors, and robotic systems generate continuous streams of quantitative data, from instrument force to motion trajectories. He emphasized that harnessing this data could transform how we evaluate and improve surgical technique.

Meanwhile, Dr. Sem Hardon highlighted how simulation-based training has begun bridging the gap. Using sensor-rich laparoscopic trainers and AI-assisted feedback, his work demonstrates that objective, data-driven assessment can accelerate learning, improve precision, and identify performance plateaus that subjective observation might miss.

.png)

Both perspectives converge to the same idea: we can make technical skill measurable.

Data Insight

Until recently, assessing technical skill required expert observation – valuable, but inconsistent, and impossible to scale.

Now that the operating room is changing, endoscopic cameras, surgical microscopes, and robotic consoles are all capturing a data-rich record of performance. As Margaux Masson-Forsythe, Head of Machine Learning at SDSC, mentioned in her Tedx Talk: hidden within these videos is an immense, untapped goldmine of data – movements, timings, tool trajectories, subtle patterns that describe how a surgery is performed.

The next question is: how can we use the data we already have?

Can we develop new metrics to quantify surgical excellence?

Can AI systems provide real-time feedback that improves performance?

Can we finally make technical proficiency a measurable component of surgical quality?

Coming next: SDSC believes the answer is yes. In Part 2, we’ll walk you through how SDSC is turning surgery from an art into a science.

1. Nepogodiev D, Picciochi M, Ademuyiwa A, Adisa A, Agbeko AE, Aguilera M-L, et al. Surgical health policy 2025–35: Strengthening Essential Services for tomorrow’s needs. The Lancet. 2025 Aug;406(10505):860–80. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(25)00985-7

2. Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? New England Journal of Medicine. 1979 Dec 20;301(25):1364–9. doi:10.1056/nejm197912203012503

3. Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EVA, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002 Apr 11;346(15):1128–37. doi:10.1056/nejmsa012337

4. Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003 Nov 27;349(22):2117–27. doi:10.1056/nejmsa035205

5. Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, Oerline M, Carlin AM, Nunn AR, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013 Oct 10;369(15):1434–42. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1300625

6. Scally CP, Varban OA, Carlin AM, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Video ratings of surgical skill and late outcomes of Bariatric Surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2016 Jun 15;151(6). doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0428

7. Stulberg JJ, Huang R, Kreutzer L, Ban K, Champagne BJ, Steele SR, et al. Association between surgeon technical skills and patient outcomes. JAMA Surgery. 2020 Oct 1;155(10):960. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3007

8. Szasz P, Louridas M, Harris KA, Aggarwal R, Grantcharov TP. Assessing technical competence in surgical trainees. Annals of Surgery. 2015 Jun;261(6):1046–55. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000000866

.png)

.png)